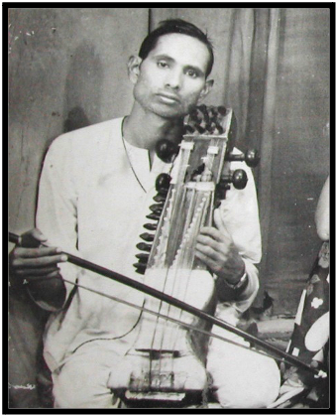

Being closest to human voice there is no instrument better than the sarangi to represent and explore the intricacies of South Asian Classical Music (SACM). It has primarily been used as melodic accompanying instrument for vocal classical music such as khayal and semi classical music such as thumri, dadra, ghazal etc.

Unfortunately sarangi players did not touch the imagination of most musicologists of 20th century, and there is hardly any musical literature available on them. The impression being created was that they are second rate musicians and only fit to accompany courtesans. Their musical knowledge and theoretical expertise are not considered great, and usually they are not recognized as authority in music (Neuman 1980: 120).

This is far from truth because many sarangi players were excellent instrumentalists, vocalists and composers, with deep and profound knowledge of the Classical Music of Subcontinent. They were the founders of power khayal gharanas like Patiala, Kirana and Indore. In addition they were the foremost teachers of female singers.

In the later half of the 20th century, musicologists like Joep Bor have written very comprehensively about sarangi and its players, but almost nothing has been written about the sarangi players of Pakistan. Despite being great musicians they were never documented and no one knows their existence and contribution in the enrichment of the music of Subcontinent.

A dire need was felt to preserve the names of these unsung heroes. The instrument is truly on the verge of extinction in Pakistan. Only a handful of sarangi players are left, five to be precise. A humble effort has been made to document as many sarangi players as possible, also keeping in mind the authenticity of the information.

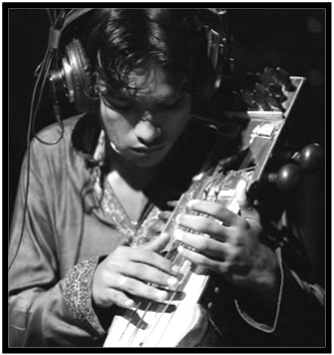

To shows the diversity and originality in the playing of Pakistan sarangi players the left hand playing techniques of the sarangi players of Pakistan has also been discussed in detail. As effort has been made to discuss the influence of the playing technique on the playing style of an individual. Video examples have been provided to further illustrate the view point.

Very little has been written on the solo repertoire of sarangi. No significant analysis could be found on the playing style or baj of sarangi players. The sarangi has primarily been used as a melodic accompanying instrument. It does not has a music making model that has evolved as a tradition. Although there are no specific bajs in solo sarangi playing, but there are individuals who have excelled as soloist and have distinct features in there solo playing. The solo repertoire of sarangi has been discussed in detail giving oral as well as written references.

Due to the dearth of written material, mostly oral references have been used. The data has been collected through audio and video interviews of direct descendants and disciples of sarangi players, during the course of extensive field work of around two years. The cities that were spanned during the course of the field work include Lahore, Kasur, Faisalabad, Gujranwala, Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Multan, Bahawalpur, Karachi and Hyderabad. The sarangi players have been grouped according to the geographical region to which they belong.

History of Sarangi

Due to variety of its forms and widespread use sarangi is believed to have originative from folk instruments of India. Modern day sarangi is the modified and improved form of chikara, gujuratan and Sindhi sarangi, which are basically rural folk instruments of Rajistan, Haryana, UP and Punjab.

As sarangi is believed to be originated from folk instrument of rural India it is very difficult to trace its history. Very little is known about folk music of India generally before the 16th century.

There are several opinions as to how and when sarangi came into being, some of them have mythological origins. Most of the Hindu sarangi players usually mentions Raavan as the inventor, but most Muslim sarangi players give credit to a learned Hakeem who saw a dried monkey skin and intestines hanging from a tree in a jungle and came up with a brilliant idea of making a sarangi.

Other musicians say that it is an import from the outside world maybe Greece or Central Asia. Some also attribute it to famous Muslim musician and poet Amir Khusrau. although there is no mention of any sarangi player in Mughal Emperor Akbar Court and in Ain e Akbari.

According to the famous writer Abdul Halim Sharar, sarangi is a recent invention in the credits of its invention goes to Mian Sarang, a court musician of Mohammad Shah Rangila. It developed with the rise of Khayal.

Some musicologists suggest that since bowing instruments originated from Central Asia this might be the case with the origin of sarangi. Kobuz, a very ancient bowing instrument of Central Asia is considered to be the fore father of 14th centuries Chinese instrument YUAN SHIH, which in turn can be considered to be the ancestor of sarangi.

Still there is no concrete evidence regarding sarangi as an import to India. One is inclined to think that since sarangi is the most authentic Indian instrument with the capacity of representing Indian music in its intricate form, it being an import is highly unlikely. As mentioned earlier the bowing instruments start appearing in Indian paintings in the 16th century. The first sarangi seen in a painting was in the 17th century. The painting depicts at least four Princes, listening to a seemingly sophisticated sarangi, being played by an old musician. It is really interesting to note that the sarangi depicted in the above painting resembles closely to the modern day Gujuratan sarangi.

According to the Musicologist D. Newman sarangi entered the classical arena in the first half of 18th century generally used as an accompanying instrument instead of Been. Because of its folk origin it entered the classical stage through rural musicians. To occupy the status of accompanists compared to just being minstrels was an upgradation for them. In the later half the same century ie 18th, its association with courtesans was also well established.

The decline of sarangi

Through this association they were able to interact with the classical music circle. It was the era when Khayal singing was at its zenith and most of these female singers were disciples of khayal singers. Sarangi penetrated the classical arena but its association with the courtesans remained as well in the 19th century. The common perception that along with tabla players they were ranked lowest in the hierarchy of musician persisted and their long association with courtesans and dancing girls relegated their social status further. They were considered neither vocalist nor instrumentalist, just accompanists. Their musical knowledge and theoretical expertise was not considered impeccable and they were not recognized as authorities on music. Ironically this all has not been true because most of the great female singers were the students of these sarangi players. Being closest human to human voice its versatility which enabled it to produce every subtle nuances of vocal music, with this soothing and attractive timber made it an ideal accompaniment to classical vocal music, particular khayal singing. By the middle of the 19th century it became the preferred company instrument to khayal and another light classical form like thumri and dadra.

It is evident from the history of evolution of sarangi that the modern day classical sarangi has its roots in rural India and is most probably evolved from folks sarangis. Historically the sarangi may have been originally a solo instrument in its own right. In the painting of the 16th, 17th and 18th century, saints, yogis and faqeers are depicted playing the sarangi and singing with it. These painting give us another perspective that in the beginning sarangi may have been associated with religious music and mostly devotional song were played on it.

However not all the fiddlers were yogis or saints. Dhadis and Mirasi who were professional folk musicians from Punjab and Rajputana used to play folks sarangi and sing with it. They were soloists in their own right. With the passage of time these professional folk musicians began settling in the cities. In the classical musical traditions rabab and been were the accompanying instruments at that time. Rabab and been had developed into sophisticated instruments and were played solo too. These rural musicians must have discovered soon that it was nearly impossible to compete with rabab and been and in order to earn their bread and butter they started to provide accompaniment to courtesans. As they could company their own singing with sarangi it was not difficult for them to company these female singers as well

But despite its significant sarangi playing has been on an incessant decline especially in Pakistan. The analysis of this of the decline of sarangi coincides with the overall desperate condition of classical music after Partition. The great musical tradition is being lost. There are several reasons of the decline of classical music in Pakistan. Lahore was an important Cultural Center in North India before Partition. Many prosperous Hindu and Sikh families were the main patrons of the classical music but after Partition most of these patterns migrated to India. There were so many Muslim artists who prefer to migrate to Pakistan from India, among them some were legendary artists like Sardar Khan (grandson of Tanrus Khan) of Delhi Gharana, Roshan Ara Begum of Kirana Gharana, Asad Ali Khan (nephew of Fayyaz Khan) of Agra Gharana, Bundu Khan of Delhi Gharana, Akhtar Hussain Khan of Patiala Gharana and some young and promising artists like Salamat Ali Khan and Nazakat Ali Khan of Shamchaurasi Gharana and Amanat Ali Khan and Fateh Ali Khan of Patiala Gharana. But in an inverse move almost all the patrons migrated to India. After a while the artists realized that the old system of patronage has completely collapsed. Although cGovt of Pakistan offered patronage through radio but it was inadequate and the artist started to suffer financially. The conditions were far better in India and it was a sad and decisive day when body Bade Ghulam Ali Khan chose to migrate to India after spending a few miserable years in Pakistan. This move resulted in the flowering of a very successful post Independence career there for Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

Actually the policies of the state of Pakistan regarding classical music have been apathetic. It has been very difficult for the artist to earn their living and they were left at the mercy of the market. In a shrinking market they gradually lost their audience. Progressively the artist started discouraging their children from choosing classical music as a profession. New forms of music were becoming popular and consequently the children of the great masters of classical music started opting for film music or ghazal singing. Presently almost all the children of great masters are into pop music. The decline of the classical music became one of the primary reasons of the decline of sarangi. Social forces and influences have been largely responsible for the decline of sarangi. As mentioned earlier in the social hierarchy of musicians, both sarangi and table players ranked among the lowest. They’re called Dhadis and Mirasis. Although sarangi and table players were equally important in the assembles of singing and dancing girls the tabla has to a great extent outgrown the stigma of association with prostitution partially because of its enhanced role and more glamorous status in the accompaniment of sitar and sarod. In popular imagination the sarangi remained linked to the world of courtesans.

The erosion of the funds of the nobility, shrinking courtesan patronage began under the British rule completed with the partition of India and Pakistan in 1947. The harmonium largely replaced the sarangi as the preferred company to vocal music although it’s temper tones are categorically out of tune for South Asian classic music. Generally vocalists shy away from the possible competition of sarangi players, as indeed sarangi players do something overplay or steal the limelight often, justifiably considering themselves to be of a more substantial musical pedigree than the singer they accompany.

Musical aesthetics have also changed during the 20th century. The use of microphones and the proliferation of recorded music have increased accessibility and public appreciation of sweet singing. The technical improvement in the sitar and sarod has contributed to the standardization of intonation with a high premium placed on slick clean music which “does not disturb”. The sarangi fits poorly into this context. Tt is not as glamorous as instrument as sitar and sarod. It is a survivor from a time when music spoke more directly to people and formal brilliance were valued more highly than its slickness and technical perfection. The modern concert going public is largely motivated by questions of status. There is no longer a high premium placed on being profoundly moved by music.

Sarangi is considered to be the most difficult instrument to play. It requires a lifetime to have reasonable control over this instrument. But the reward which players get in return is shamefully minimal. they’re considered neither vocalists nor solo instrumentalist. Lack of recognition had eroded their self-respect bringing about a decline in the dedication with which the tradition is sustained through practice and teaching and inevitably a decline in musical excellence. There had been many excellent players who due to their depressing economic prospects has become unmotivated with regard to the tuning and maintenance of their instruments. This compounds that dimness of the prospects of employment as well as inviting criticism for vocalist and from the musical public which further eroded self-respect. A large proportion of hereditary sarangi players are no longer teaching their sons. Disillusioned by the economic prospects offered by sarangi playing many are sending their sons to school in commercial colleges.

These social and economic factors have forced the sarangi players not to transfer this great art to the next generation. Thus a glorious musical tradition is on the verge of extinction especially in Pakistan.

Sarangi Players of Pakistan

It is generally believed that the tradition of classical sarangi playing originated from Panipat, Sonipat, Jhajjar and Kirana, all small towns around Delhi. The early great sarangi players, who we know through oral and written history, also belong to these areas.

The sarangi players of Pakistan can be grouped under two major categories i.e. the players that migrated from India after Partition and the players that belong to the areas comprising Pakistan.

Lahore and Kasur are two regional centers in Pakistan that have produced the largest number of sarangi players. The musicians of Lahore claims that their ancestors belong to Lahore for more than two hundred years. These include vocalists as well as instrumentalists. The instrumentalists were mainly sarangi and tabla players.

Kasur on the other hand has even deeper roots in music that date backs to the time of Emperor Mohammad Shah Rangila (ghulam haider 2006:13). Some historians even believe that Mian Tansen often used to visit Kasur and with this reference Kasur was also called Choti Gawalior, literally meaning Small Gawalior (Khan & Sheikh 2006:12).

The musicians of Kasur were diverse in the sense that they were not only vocalists, but also binkaars, sarangi players and tabla players. It is said that Budday Khan of Kasur was born in eighteen fifteen which places him in the age group of Haider Buksh of Panipat, who is believed to be the founder of classical sarangi.

Apart from Lahore and Kasur, Karachi, Faisalabad, Multan, Gujrawala, Sialkot, Hyderabad and even smaller towns had also produced sarangi players, though not in significant numbers. As sarangi was an accompanying instrument of the courtesans, wherever there were courtesans usually there were sarangi players.

The sarangi players that came to Pakistan after Partition include players from East Punjab, Rajhistan, Haryana, Utter Pradesh, Delhi and its surrounding cities. The sarangi players that came from the towns of East Punjab like Amritsar, Jalandhar, Hoshiarpur and Ludhiana mostly settled in Lahore, Faisalabad, Multan and Rawalpindi. On the other hand the sarangi players that came from Delhi, Muradabad, Rajhistan, Haryana and Utter Pradesh mostly settled in Karachi and Hyderabad.

Though there are various schools of sarangi playing but apart from Delhi Gharana of Mamman Khan, there are no recognized gharanas in sarangi playing. The term gharana in the contemporary sense means belonging to a particular area, following the same playing technique and style.

Construction of Classical Sarangi

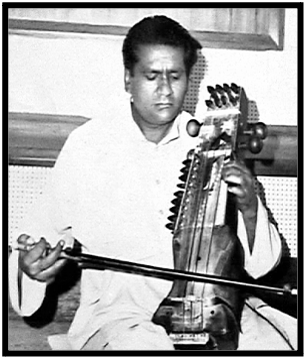

Sarangi is the premier bowing instrument of the subcontinent. The modern classical sarangi is roughly two and a half feet long, carved out from a single piece of wood preferably of Tun. Other woods have also been used like Mango and Burma teak, but in durability and good sound quality were not an improvement over Tun wood. There is still no standardization regarding the making of sarangi and it is said as an adage that no two sarangis are alike.

The classical sarangi consists of three parts: the belly, the chest and the head. The belly is hollowed out in the front and covered with goat skin. The chest and the head are hollowed out from the back and consists of peg boxes. The belly has an irregular shape and is more inwardly curved in the left side due to the extended width of the chest. It has three main playing strings made of gut and thirty five to thirty eight sympathetic metal strings. The strings are passed over and through an elephant shaped bridge usually made of bone of ivory or camel bone. This bridge rest on a leather strap which protects the instrument’s goat skin face. The right side of the chest contains twenty four wooden pegs for tuning the sympathetic strings. Out of these twenty four resonating strings, fifteen are tuned chromatically and nine are tuned according to the scale being played.

These sympathetic strings are usually made of thin gauge steel. The resonating strings attached to the eleven frontal pegs mounted in the upper pegbox or head, are passed through two flat bridges, known as the Jawari bridges. These strings are also tuned according to the scale being played The bow held with an underhand grip is usually made of Rosewood or Ebony with Black horse hair and is considerably heavier than western violin or cello bows, contributing to the solidity and vocal quality of the sarangi’s sound.

The sarangis three melodic strings are stopped not with the pads of the fingers but with the cuticles or the skin above the nails of left hand. There is no other instrument on which the strings are stopped with so high a portion of the back of fingers. Practice often leads to prodigious callusing as well as telltale grooves in the fingernails. The difficulty of playing sarangi is legendary.

The instruments used by sarangi players are between fifty to hundred years old, often inherited from their elders. The instruments tone and playability are largely determined by its make and setting up; the placement and contouring of the jawari bridges, the thickness and height of the main gut and sympathetic strings, the thickness of the goat skin etc. These complex skills require a lot of experience. Traditionally they have been passed like the music, from grandfather to father and to the children. But these skills are gradually being lost due to the decline of sarangi itself.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM AMRITSAR

Hussain Buksh

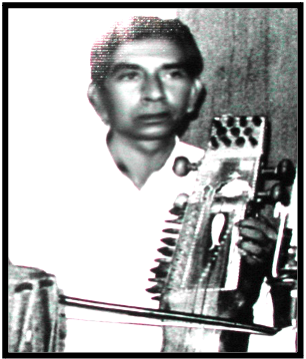

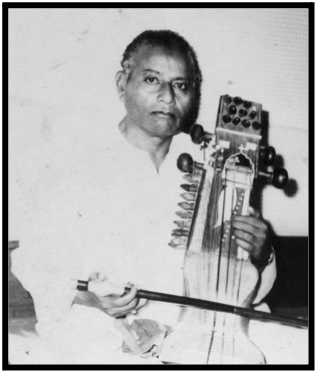

Hussain Buksh of Amritsar, the grandson of Baba Umera, born in Amritsar in 1902 got his initial training in sarangi playing from his father Fateh Din and Uncle Sain Ditta. Later he became the formal disciple of Peeran Ditta, an eminent sarangi player of Jhalandhar. Hussain Buksh was also greatly influenced by famous sarangi player Shakoor Khan of Kirana Gharana. Hussain Buksh was a good accompanist but his real forte lay in playing solo sarangi. He also served in HMV. After Partition the family shifted to Lahore where he worked in Radio Pakistan Lahore and in the film industry. He also accompanied many great singers of his times. He was a great teacher and had many distinguished students like Abdul Hameed Khan, Pheeru Khan, Nisar Ali Khan, Murad Ali and many others. He died in Lahore in 1984.

Nathu Khan

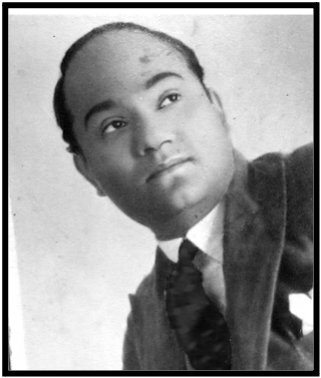

The legendary Nathu Khan, born in Amritsar in 1920 was the son of Baba Ballay, a tabla player. He got his initial training in music and sarangi playing from his paternal uncle Baba Ferozdin, the disciple of a family elder Baba Ali Buksh, who in turn was the disciple of Maula Buksh of Talwandi Gharana. Later Nathu Khan became the formal disciple of the great Ahmadi Khan of Delhi and Maula Buksh of Talwandi Gharana. After Partition he migrated to Pakistan and joined Radio Pakistan Peshawar. Later he was transferred to Radio Pakistan Karachi as a staff artist.

Nathu Khan was amongst the finest sarangi player of his times and was the master of rhythm. He was a great soloist and a great accompanist and played with the great vocalists like Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Salamat Ali Nazakat Ali, Ashiq Ali Khan, Roshanara Begum, Umeed Ali Khan, Amanat Ali Khan, Fateh Ali Khan, Chotay Ghulam Ali khan etc. Ustad Salamat Ali Khan gave him the title of “camera”, thus admitting his genius as an accompanist. He traveled world over and got international fame and recognition. He was also good composers using the name N.K Naser and composed for radio and films. In the mid sixties Nathu Khan joined PIA Arts Academy as a composer and musician and died in Munich in 1971 during one of his international tours. His sons Mujahid Hussain and Nasir Hussain are distinguish composer and guitarist respectively.

Mallo Khan

Mallo Khan born in Amritsar in 1918 was the first cousin of the legendary Nathu Khan. His father Ghulam Qadir alias Qamhay Khan was a tabla player. Mallo Khan learned sarangi from his paternal uncle Baba Ferozdin, who was the disciple of the maternal grandfather of Mallo Khan named Baba Ali Buksh. Incidentally Baba Ferozdin was also the music teacher of Nathu Khan. Mallu Khan was a very accomplished sarangi player who specializes in playing in geet, ghazal, thumri and other light classical forms. He accompanied mostly courtesans. He also worked in films and theaters. Mallo Khan died quit young just after Partition.

Nasir Ali Khan

Nisar Ali Khan belonging to Amritsar clan of sarangi players was born in Amritsar in 1924. His father Ferozdin, a sarangi player learned this difficult art from Saeen Ditta. Nisar Ali Khan got his initial training in sarangi playing from his father and Saeen Ditta, later he became a formal disciple of Hussain Buksh Khan of Amritsar. Nisar Ali Khan, an accomplished sarangi player who specializes in light classical genres like geet, thumri and ghazal, played in concerts and worked in Pakistan television and films. He was a good teacher and taught music to many courtesans of Lahore. He died in 2003.

Pheru Khan

Son of Fateh Din, Pheeru Khan, and the youngest brother of Hussain Buksh started learning the art of sarangi playing from his uncle Saeen Ditta. After his death, he learned from his elder brother Hussain Buksh. He was a very sweat and melodious sarangi player. His forte was playing the light genres like thumri, dadra, ghazals and geet etc. He played on Pakistan Television, films and in private mehfils. He died in the early nineteen nineties in Lahore.

Abdul Hameed

Born in 1928 in Amritsar, Abdul Hameed was another eminent sarangi player from Amritsar. Abdul Hameed started learning sarangi from his uncle Hussain Bakhsh. After Partition, Abdul Hameed joined Radio Pakistan Karachi as a staff artist, and then at Central Production Unit in Lahore. He accompanied many great vocalist of his time like Umeed Ali Khan, Salamat Ali Nazakat Ali, Amanat Ali Fateh Ali, Roshanara Begam etc. His field of expertise was accompanying classical vocalist. He died in 1994 in Lahore.

Allah Rakha Khan

Allah Rakha Khan was born in Sialkot District, in 1932. His father Ustad Lal Din Khan was a sarangi player of repute who used to live and work in Amritsar. He acquired his initial education in classical music and sarangi playing from his father. As a teenager he bacame a formal disciple of the famous Ustad Ahmadi Khan of Delhi. After his death, Allah Rakha became the disciple of his childhood inspiration, the illustrious Nathu Khan of Amritsar. He also polished his sarangi playing skills from Ustad Alladiya Khan of Delhi.

After Partition, Allah Rakha Khan migrated to Pakistan, settled temporarily in Karachi, moved to Lahore in 1954 and for almost two decades worked at the Radio Station, Television and in the film industry. He moved to Rawalpindi in 1968, and became a regular employee of Radio Pakistan, Rawalpindi, where he served till his retirement in 1992. In 1994, he was awarded the Pride of Performance for his lifelong devotion to classical music.

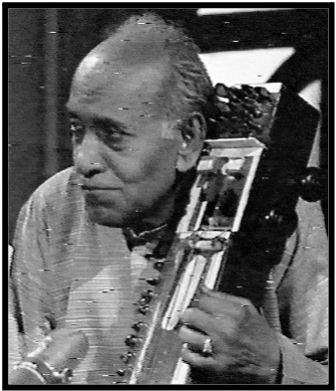

Ustad Allah Rakha the last living master of the sarangi in Pakistan is a very accomplished sarangi player with equal proficiency in playing almost all the genres of our music like classical, light classical, ghazal, geet, folk etc. He is accomplished solist and has accompanied almost all the leading singers of Pakistan.

Faqeer Hussain

Faqeer Hussain currently amongst the leading sarangi players of Pakistan was born in Ludhiana in 1934 in a family of musicians who were mostly sarangi and tabla players. His father Kher Din and grandfather Allah Buksh were both sarangi players who used to work in Amritsar. He got his initial training in sarangi playing from his father. Later he went to Faisalabad, a hub of musicians after Partition where Faqeer Hussain spent thirteen years learning sarangi from his peers. He spent time with the famous Alladiya Khan of Delhi, and polished his sarangi playing. Though Faqeer Hussain learned sarangi from different sources, but Nathu Khan remained his chief inspiration. He became formal disciple of the legendary Nathu Khan in Lahore in the mid 1960’s. Faqeer Hussain joined Radio Pakistan Lahore in 1998 as a staff artist and is still serving there.

Khawar Hussain

Khawar Hussain currently the torch bearer of Amritsar clan of sarangi players was born in Lahore in 1959. His grand father Aziz-u-Din used to play sarangi and was the disciple of Fateh Din (father of Hussain Buksh). His father Abdul Majeed was a tabla player. Khawar Hussain was initially a violin player but in order to carry the great tradition of his elders, became the disciple of Pheeru Khan in the mid eighties. He is now the leading sarangi player in the country specializing in the light genres like geet and ghazals. He has accompanied most of the current leading singers of the country. He also plays solo sarangi and works in film and television.

Taimur Hussain

Born in 1975 in a non-musical family Dr Taimur Khan started learning sarangi from Ustad Mubarak Ali Khan of Jalandar in 1997. After the death of Mubarak Ali Khan in 2002, Taimur Khan started taking musical lesson from Mehfooz Khokhar. In 2004, he became formal disciple of Ustad Allah Rakha Khan. Apart from giving private and public performances Taimur Khan is also associated with Radio Pakistan Rawalpindi.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM BHAWANI

Ghulam Nabidad Khan

Ustad Ghulam Nabi Dad Khan, born in Bhawani, district Hisar in 1884 got his training in music from his father Ustad Qalandar Buksh who was a known dhrupad singer and court musician of Bharat Pur. Later he became a formal disciple of the illustrious Ustad Umraao Khan (son of Tanrus Khan) of Delhi Gharana. After the death of his father, Ustad Ghulam Nabi Khan became the court musician of Bharat Pur.

On the insistence of his spiritual guru, Pir Raza Shah Gillani, Ghulam Nabi shifted to Multan from Gawalior State where he was court sarangi player. In Multan he settled in Haram Gate and started spreading his vast knowledge of music to others. Ustad Ghulam Nabidad Khan was great musician having an in-depth knowledge of classical music of Subcontinent. He was a great teacher and his disciples include both vocalists and sarangi players which include Ustad Abdul Majeed Khan of Mewat, Ustad Sharif Khan, Faqeer Hussaain of Chuna mandi Lahore, Surayya Multanikar, Iqbal Bano, Iqbal Sabira, Zareena Begum, and many others.

Sharif Khan

Sharif Khan was born in Bhawani, District Hisar in 1925 in a family of sarangi players. His father Pir Mauj and grandfather Rahim Buksh were both sarangi players. Some of his ancestor also lived in Panipat, and were disciple of the legendary Haider Buksh Khan, considered to be the pioneer of classical sarangi playing.

When Sharif Khan was nine years old he was sent to Delhi to further learn the art of sarangi playing from his uncle Hussain Buksh TT Waley. Later on he became a formal disciple of Ustad Gulam Nabi Dad Khan. Later he had the privilege of receiving guidance under Ustad Tanrus Khan’s grandson, the illustrious Ustad Sardar Khan.

After Partition Sharif Khan settled in Multan. He was a very accomplished sarangi player and worked as a soloist as well as an accompanist. He was associated with Radio Multan but he performed in all the major broadcasting centers. He accompanied many great singers of his times. He died in Multan in 2009.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM BHODIPOTRA, MULTAN

Hussain Buksh

Hussain Buksh born in Multan in 1937 was the only son of Baba Ghulam Mohammad alias Baba Gamu, who was a tabla player of repute and the disciple of Mian Faqir Buksh (father of Mian Qadir Buksh of Punjab Gharana). He learned the art of sarangi playing from his paternal uncle Ustad Ameer Allah Wasaya Bhodi Potra. Ustad Hussain Buksh was a very accomplished sarangi player and worked not only in Radio Multan but also accompanied many classical and light classical vocalists of repute. He was a great music teacher and the list of his disciples includes Surraiya Multanikar, Pawan Mushtaq, Qamar Iqbal, Malang Ali, Fakhar Hussain Baghdadi, Malang Ali Baghdadi, Nazakat Ali Baghdadi, Maqbool Khan and Wajid Ali. He remained in Multan throughout his life and died in 2007.

SARANGI PLAYERS OF DELHI GHARANA OF TABLA AND SARANGI

Ahmadi Khan

Ahmadi Khan, born in 1890 in Delhi hailed from the prestigious Delhi Gharana of tabla players. He was the son of tabla player Qalb-e-Ali alias Kale Khan and younger brother of Khalifa Gami Khan, and was groomed in the intricacies of the Pakhawaj. During his youth, he took a liking to sarangi and started his training under his maternal uncle Ustad Nazeer Khan, who was the father of another renowned saranginawaz Ustad Zahoori Khan. He also learned the intricacies of classical music from Ustad Maula Buksh of Talwandi. Following his training, Ahmadi Khan left Delhi and spent a lengthy period in Amritsar and Lahore and became one of the foremost sarangi players of his times. He was a great soloist and accompanist. He was associated with All India Radio Lahore throughout his life and died in 1945.

Ustad Ahmadi Khan was also a great teacher; his disciples include such great names as Ustad Nathu Khan, Ustad Allah Rakha, Imdad Huddain Khan and many more. Ahmadi Khan’s son is the distinguished sitarist, Ustad Imdad Hussain Khan of Karachi.

Zahoori Khan

Zahoori Khan who belonged to the famous Delhi Gharana of tabla and sarangi players was born in Delhi around 1910. Zahoori Khan learnt the art of sarangi playing from his father, Ustad Nazeer Khan and quickly achieved mastery over this difficult instrument and performed with all the leading musicians of the sub-continent. He also worked at All India Radio, Delhi. Following Partition, Zahoori Khan migrated to Karachi and joined Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation as a staff artist and regularly broadcasted solo performances and also accompanied the major singers of his times like Salamat Ali Khan, Nazakat Ali Khan, Umeed Ali Khan, Roshan Ara Begum, Amanat Ali Khan, Fateh Ali Khan etc. The maestro passed away in 1964 at the age of fifty four. He also recorded a number of EP records. His three sons Zahid Hussain, Zakir Hussain and Sabir Hussain reside in Karachi and are renowned musicians in their respective fields.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM DELHI GHARANA OF MAMMAN KHAN

Bundu Khan

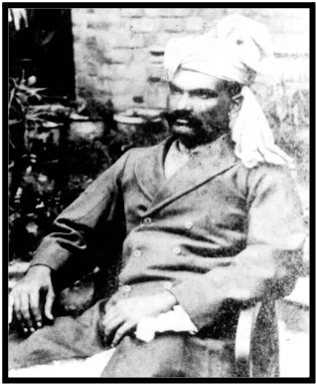

Bundu Khan the nephew and son in law of Mamman Khan is regarded as the most accomplished of all sarangi players and one of the greatest musicians of 20th century. Bundu Khan born around 1880 in Delhi received vigorous training from his maternal uncle Mamman Khan. He was open to knowledge from all sources and benefited from many great musicians of his era.

In his early twenties he went to Indore with a female singer as an accompanist. He got instant recognition there as being a great sarangi player. He was immediately appointed court musician. It marked the beginning of a long and extremely successful career. Bundu Khan accompanied many great singers of his times like Miyan Allabande Khan, Zakiruddin Khan, Alladiya khan, Umraao khan, Faiyaz Khan, Vilayat Hussain Khan, Ali Buksh of Patiala, Mian Jan Khan, Karamat Khan of Jaipur, Rajab Ali Khan, Mushtaq Hussain Khan and host of others.

Bundu Khan’s contribution in raising the status of sarangi as a solo instrument is immense. The essence of his sarangi playing is clarity and simplicity. He also wrote a book on music named Sangit Vivek Darpan, which gives us an insight into his vast knowledge of compositions, genre and style.

Bundu khan migrated to Pakistan in nineteen forty eight, along with his sons Umrao Bundu khan, Buland Iqbal and wife. He died in 1955 in Karachi. His main disciples were late Abdul Majid Khan, Sagiruddin Khan and his two sons, late Umrao Bundu Khan and Buland Iqbal.

Umraaoo Bundu Khan

Son of the legendary Ustad Bundu Khan, Umraao Bundu Khan born in 1927 in Delhi was taught by his father and maternal grandfather, the great Mamman Khan. Young Umraao Bundu Khan began his musical training in sarangi playing and classical singing by his maternal uncle Chaand Khan. So apart from being an excellent sarangi player, he was also a very accomplished vocalist, a feat that only few individuals have accomplished. Soon after Partition the family migrated to Pakistan where he joined Radio Pakistan Karachi in 1948 and remained associated with it till his death. Apart from his artistic excellence, Ustad Umraao Bundu Khan was also a great teacher as dozens of professional and non-professional were able to learn the art from him. The maestro died in 1980 in Karachi.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM ROHTAK, HARYANA

Ghafoor Khan born in Rohtak, Haryana in 1944 was associated with Radio Karachi, the PIA Arts Academy and later with Karachi Arts Council. Apart from the sarangi, he was also proficient on the mandolin and mostly played in the orchestra. He was an excellent instrumentalist & had also conducted tours as part of cultural delegations to the UK and Japan. Ghafoor Khan passed away in 2006 in Karachi. Ghafoor Khan’s elder brother Husain Bakhsh was also a sarangi player settled in Agra Taj Colony in Old Karachi. Hussain Bakhsh a very knowledgeable musician and was teacher of many courtesans of Karachi. He also played in film orchestra.

Hussain Buksh

Hussain Buksh

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM NARNAUL, HARYANA

Shamsuddin Khan

Shamsuddin Khan born in Narnol in the mid 1920’s learned the art of sarangi playing from Shameer Khan. Prior to Partition he used to travel and perform in Mumbai, Pune, and Culcatta etc. After Partition he settled in Hyderabad Sindh. Shamsuddin Khan was an accomplished sarangi player and worked in Radio Pakistan Hyderabad and Quetta. He died in the late1990’s.

Father of famous vocalist Ustad Ameer Khan of Indore.

Niazu Khan

Belonging to the Narnol clan of sarangi players Niazu Khan was a well known and respected sarangi player. He was associated with radio Pakistan Hyderabad and accompanied famous vocalists of his times like Umeed Ali Khan, Ghulam Rasool Khan, Fateh Ali Khan of Gawalior, Salamat Ali Khan, and Roshan Ara Begum etc. He learned sarangi from his elders but later became a formal disciple of illustrious Bundu Khan. He died in the mid 1980’s at an age of 70.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM HOSHIARPUR

Ghulam Mohammad Khan

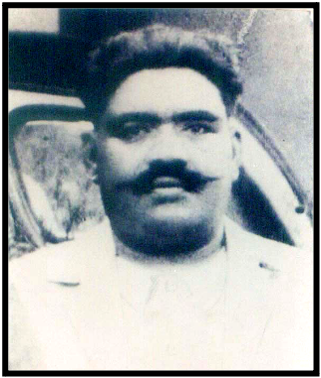

Ghulam Mohammad Khan was born in Hoshiarpur in 1910 in a family lineage of eminent sarangi and tabla players. He started learning sarangi at a very young age from his father Bahadur Ali alias Babu Khan. After his father’s death he continued learning this difficult art from his maternal uncle Ghulam Hussain Khan. Later he became a formal disciple of the illustrious Mamman Khan of Delhi Gharana and also of Raheem Buksh Shamapuri. From a very early age he was a very skillful and melodious sarangi player, and attended many music conferences and accompanied great vocalist of India like Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Bhimsin Joshi, Abdul Waheed Khan, and Amir Khan etc. He was a regular accompanist of Rasulan Bai. In the mid forties he became court musician of Hyderabad Deccan. He accompanied Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan quite frequently in Hyderabad in the early sixties. Ghulam Mohammad migrated to Pakistan in 1964 and settled in Chak Jhumra, a small town in Punjab. Soon he became an artist of Central Production Unit in Radio Pakistan Lahore. In Pakistan he accompanied almost all the great classical vocalists. He was also an accomplished solo sarangi player. He died in 1974 on the premises of Radio Pakistan Lahore. Ghulam Mohammad Khan’s sons Ghulam Sabir Khan and Ghulam Jaffer Khan are respected vocalists in Faisalabad. His grandson, Akhtar Hussain is carrying his tradition of sarangi playing in Karachi.

Interview of his sons Ghulam Sabir and Ghulam Jaffer by Ali Zafar, June 2009, Sargodha Road Faisalabad.

Ashiq Hussain Hoshiarpuri

Born in 1918 Ashiq Hussain Khan was a disciple of Ustad Alladiya Khan of Dehli and Ustad Ghulam Mohammad Khan of Hoshiarpur. He learnt the art of sarangi playing from his father Maula Buksh, a renowned sarangi player of the region and disciple of Alladiya Khan of Delhi. Later Aashiq Husaain became a formal disciple of Allahdiya Khan. Ashiq Hussain Khan was also an expert harmonium player and was noted for his command over classical music and his skill over both the sarangi and harmonium. Regarded as a very knowledgeable musician, Ashiq Hussain passed away in Sukkur in 1978.

Munshi Ghulam Ali Khan

Munshi Ghulam Ali Khan, born in Hoshiarpur in 1930, got his initial training in music and sarangi from his father Iqbal Buksh and his maternal grandfather Mola Buksh. Seeing his interest and talent in sarangi playing, his father made him the disciple of Alladiya Khan of Delhi. After Partition he moved to Multan, and remained the front ranking sarangi player in Multan for almost four decades. In 1965 he became disciple of Ustad Salamat Ali Khan of Shamchaurasi Gharana. Ustad Munshi Ghulam Ali Khan was a very accomplished sarangi player and accompanied great classical singers of his times. When Radio Pakistan was launched in Multan in 1970 he became its staff artist till his death in 1987. His son Shafqat Ali Khan also a very talented sarangi and harmonium player is carrying forward the great tradition of his father in Multan.

Tasaddaq Hussain

Tasaddaq Hussain was born in Hoshiarpur in 1945. His father Gul Mohammad, and grandfather Babu Pambu Khan were both sarangi players. After Partition his family settled in Faisalabad. In the mid nineteen sixties Tasaddaq Hussain became a formal disciple of Ghulam Mohammad Khan of Hoshiarpur.

In the late sixties, he went to Islamabad, where he worked in Central Production Unit (CPU) and accompanied singers of the merit of Umeed Ali Khan, Salamat Ali khan, Tufail Niazi, and Ijaz Hussain Hazravi. He also worked for Lok Virsa and PTV. In1979 he joined Radio Bahawalpur as a staff artist and is still serving there.

For the last decade and a half he has concentrated more on harmonium due to continuing decline of sarangi playing in Pakistan. During the span of his career he accompanied both classical and light classical singer.

Akhtar Hussain the grandson and disciple of the illustrious Ustad Ghulam Mohammad Khan of Hoshiarpur was born in Hyderabad Deccan in 1958. He performs in classical music concerts, accompanying the major classical and light classical vocalists of Pakistan. He has recently relocated to Karachi from Khairpur, Sindh in 2004, where he was employed at Radio Pakistan. He is now the front ranking sarangi player in Karachi. He has also initiated his son Gul Mohammad in the art of sarangi playing.

Akhtar Hussain

Gul Mohammad

Shafqat Ali

Born in Multan in the mid nineteen sixties, Shafqat received his training of music and sarangi playing from his father Munshi Ghulam Ali Khan. Shafqat is currently employed at Bahauddin Zikriya University, Multan as a music teacher. He also works in Radio Pakistan Multan as a musician.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM JAIPUR

Ghulam Mohiyuddin Khan

Ustad Ghulam Mohiyuddin belonged to the eminent Jaipur Gharana of sarangi and tabla players. Born in 1936 in Sikkar, Jodhpur, Ghulam Mohiyuddin learnt sarangi from his father Hameed Khan and grandfather Khaaj Bakhsh Khan. There are many famous sarangi players in their family, notable among them are Munir Khan, Raapat Khan, Hans Raj Ji, Ustad Sultan Khan and Ustad Fakhruddin Khan. Late sitar wizard Ustad Kabeer Khan was also closely related to Ghulam Mohiyuddin.

Ghulam Mohayuddin an excellent sarangi player accompanied almost all the great singers of his times. He remained associated with Radio Pakistan Karachi for about forty years till his death in 1993. He also regularly performed on Pakistan Television programs.

Noor Khan Noor Khan

Ustad Noor Khan belonged to the Jaipur Gharana. His maternal grandfather Khaaj Bakhsh Khan and all other family members from Noor Khan’s mother’s side were well established musicians, mostly sarangi players. Noor Khan first learnt sarangi from his maternal grandfather Khaaj Baksh Khan and then from his maternal uncle, Mandaari Khan of village Raseed-Paraa near Sikkar. Noor Khan joined Radio Pakistan Karachi station in 1964 and gradually rose to the level of senior musician. Ustad Noor Khan also regularly accompanied vocalists in the daily live programs of light music comprising geet and ghazal. He died in 1989. Ustad Noor Khan’s son Islamuddin plays violin and is also a good vocalist.

Jamaal Khan

Jamaal Khan, born in 1912 in Charaawa in Jaipur State got his initial training in music and sarangi playing from his father Allah Diya Khan, a court musician in the Jaipur State. Later he became a formal disciple of famous sarangi player Mohammad Azeem Khan Narnaulee. Before migrating to Pakistan he performed in Delhi, Meerut, Lucknow, and many princely states. After Partition, Ustad Jamaal Khan settled in Nawaab Shah, Sindh. He was employed by Radio Pakistan Karachi for two years; subsequently he was transferred to Radio Pakistan Quetta as composer and sarangi player. In Quetta, he composed many popular tunes. Jamaal Khan also played excellent harmonium. Jamaal Khan’s was also the music teacher of his two younger brothers, the distinguish singer and composer Nihaal Abdullah and tabla player Hussain Buksh. Jamaal Khan died in 1995 in Nawabshah.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM JALANDHAR

Peeran Ditta

Born in Jalandhar in 1889 Peeran Ditta was the disciple of the famous sarangi player Ustad Alladiya Khan Birtuwala. The sarangi players of this region believed that he was the first artist who brought khayal ang of sarangi playing to Punjab. Before him the jor ang of sarangi playing was prevalent amongst the sarangi players of Punjab. He used to play and practice in Laryan Wala Takya in Amritsar, a place famous for its musical concerts. Peeran Ditta accompanied many great singers. He seldom went out from Amritsar and Jalandhar. He was a great teacher and has such distinguished disciple as Hussain Buksh of Amritsar, Faiz Mohammad, Fazal Elahi and many others. He died in Lahore in 1951.

Jor Ang was inspired by Dhrupad. It does not have much behlawas, and the use of bow is excessive and multiple notes per bow are not common. It is useful in playing gamaks and fixed compositions on sarangi.

Faiz Mohammad Khan

Faiz Mohammad was born in Jalandhar in 1910. His father Ali Bukhsh was also a sarangi player. Faiz Mohammad got his initial training in sarangi playing from his maternal uncle Ustad Peeran Ditta Khan. Later he became a formal disciple of the famous Allahdiya Khan Birtuwala at an age of only eighteen. After Partition Faiz Mohammad got himself associated with Radio Pakistan Rawalpindi as a staff artist in 1951. During this decade he not only accompanied many great singers but also went on foreign tours to Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Nairobi and other African countries. In 1964 he got associated with Radio Pakistan Karachi, in 1969 with Radio Pakistan Dhaka and in 1974 with Radio Pakistan Rawalpindi.

Faiz Mohammad was a very good accompanist and an able soloist. He accompanied many great singers of his times. Faiz Mohammad died in 1964.

Fazal Elahi

Fazal Elahi was born in Jalandhar in 1912. His father Rahim Buksh was a well known sarangi player of Jalandhar. In his younger years Fazal Elahi worked in films and theater as an actor. Fazal Elahi started learning sarangi in his late twenties. His initial music teachers were his father and his maternal uncle Ustad Peeran Ditta. Later he became a formal disciple of famous binkar Ustad Abdul Aziz Khan, who himself was initially a sarangi player and the son of famous sarangi player Ustad Alladiya Birtuwala. After Partition he left acting and made sarangi playing his sole passion. He was a specialist in playing light classical genres like thumri, ghazal and geet on sarangi. He was also associated with the Pakistan film industry as a musician. Fazal Elahi accompanied and taught many courtesans of his times. He died in Lahore in 1973.

Mubarak Ali Khan

Born in Jalandhar in 1931 Mubarak Ali Khan was initiated in sarangi by his father, Ustad Jhanday Khan. Mubarak Ali Khan was orphaned at the age of nine and sought the tutelage of Ustad Alladiya Khan of Delhi, who was also his father’s teacher. This apprenticeship lasted until Partition when Mubarak Ali Khan left India for Lahore. In 1948 he became the disciple of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and spent some time accompanying him in Pakistan and on his tours to India. Mubarak Ali Khan was associated with Radio Pakistan, Rawalpindi for twenty seven years and regularly accompanied the likes of Roshan Ara Begum, Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ustad Umeed Ali Khan, Ustad Salamat Ali Khan, Amanat Ali, Fateh Ali, Chotay Ghulam Ali Khan and Ghulam Hassan Shaggan. The Government had awarded him the Pride of Performance and Sitara-e- Imtiaz in 2001. The maestro passed away in 2002.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM KASUR

Bade Buddhay Khan

Said to have born in 1815, Buddhay Khan was considered a formidable exponent of the sarangi amongst the musicians of Punjab. He was also a good vocalist and tabla player. He received his early training in music from Mian Hassu Gama, before becoming the disciple of Ustad Dilawar Ali Khan of Rewa, before returning to Lahore where he performed with all of the great musicians of the time. He also composed a number of bandishes under the pseudonym of Gyan Hans Ras. He was the grandfather of Ustad Chotay Ghulam Ali Khan. His renowned disciples include Mian Ghulam Mohammad Khan, Peeran Ditta Jaferkotia, Mian Kheraat Ali, and Ghulam Haider. He died in 1929 and is buried in Kasur (Khan & Sheikh 2006: 23).

For words in italics consult glossary of terms.

Ghulam Mohammad Khan

Ghulam Mohammad Khan received his initial training in music and sarangi playing from his father, Ustad Haji Amir Bukhsh Khan, a renowned sarangi player of Kasur. Later he became a formal disciple of the famous binkar Ustad Buddhay Khan of Kasur. When Ustad Allah Bande Khan of the Dagar Gharana performed at the Takia Meerasian Lahore, Ghulam Mohammad Khan was also invited to perform. His accompanying and renditions won him a lot of fame and appraisal. He died in 1950 in Lahore. Khurshid Bai Hijrowali was his famous disciple (Khan & Sheikh 2006: 16).

Haider Buksh Faloosa

Haider Buksh Faloosa born in Kasur in 1896 got his training in music and sarangi playing from his father Ustad Bade Chajju Khan. Initially Faloosa Khan was associated with theater and also worked in the film industry. When Radio Pakistan Lahore was launched he was amongst the very first sarangi players to join it. Haider Buksh Faloosa participated in numerous music conferences and got himself recognized as a very melodious and skillful sarangi player by accompanying almost all the great vocalists of his times. Ustad Haider Buksh considered very melodious and soulful sarangi player was an expert in playing light classical genres like thumri, geet, ghazal, and folk etc. He died in 1961 in Lahore. Fateh Din was his only disciple in sarangi playing (Khan & Sheikh 2006: 46).

Fateh Din

Fateh Din born in 1912 in Kasur was the grandson of Mian Elahi Buksh, a court musician of Malwaal State. He received his early training in sarangi from his father Baba Kalu Khan, who was also a known sarangi player of Kasur. Later he became the only disciple of Ustad Haider Buksh Faloosa.

Apart from being an excellent sarangi player, he was also a good singer. He accompanied mostly coutesans and also played in films. He was the teacher of Elahi Jan Fazilkawaali, Zohri, Akhtari, Kurshid Pondwaali, and filmstar Meena Chaudhry.

He died in 1974 and is buried in Kasur (Khan & Sheikh 2006: 62).

Chotay Kale Khan

Chotay Kaley Khan was the disciple of Umraao Khan (son of Tanrus Khan). Apart from a very good sarangi player Chotay Kale Khan was also a good singer. He was a very knowledgeable musician. Eidan Bai Hasyanwali was amongst his famous disciple (Khan & Sheikh 2006: 18).

Ghulam Ahmed Khan

Ghulam Ahmed Khan born in Kasur in 1908 learned the art of sarangi playing from his father Mian Chajju Khan. He was an expert in playing light genres like thumri and geet. He mainly worked in the films as a musician with reputed music directors such as Khawaja Khursheed Anwar, Rasheed Atre, A.Hameed etc. Amongst the last reknown sarangi players from Kasur, he died in 1982.

The musical teacher of Chotay Ghulam Ali Khan

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM LAHORE

Nikkay Khan

Ustad Karim Buksh alias Nikkay Khan, a very well known sarangi player of Lahore of the late 19th and early 20th century learned sarangi from his father Baba Umer who was also an accomplished sarangi player. He was a contemporary of Ali Buksh and Fateh Ali of Patiala and accompanied them and many other many great singers of his era. He performed all over the subcontinent. He was a great teacher; amongst his famous disciples being his son Rahim Buksh, grandson Nazim Ali Khan and Fazal Khan of Shahalmi.

Mian Billay Khan

Billay Khan, real name Meeran Bukhsh, a well known musician within the music circles of Lahore was born in Lohari Gate Lahore. He was the disciple of the distinguished Ustad Fateh Ali Khan of Patiala. He performed with all the leading vocalists and songstresses of Lahore including Zebunissa, Khurshid Bai and Anwari Bai. He was also a keen stage actor and later settled in Quetta and unfortunately became one of the victims of the 1935 earthquake. Amongst his disciples was his son Barkat Ali, a talented sarangi player associated with the Pakistani film industry.

Bahar Buksh

Bahar Buksh, born in Lahore in 1890 was an accomplished sarangi player, a good vocalist, and an able composer. He received his initial music training from his father Nabi Buksh. Later he became a formal disciple of the Aashiq Hussain Khan, the famous sarangi player of Panipat. He played sarangi in films, theater and accompanied great singers of his times. He was the father and teacher of famous music director Akhtar Hussain Akhiyan and Mohammad Aashiq Hussain, the paternal uncle and inspiration of famous music directors Master Abdullah and Master Inayat Hussain, the maternal grandfather of famous music director M. Ashraf and violinist Talib Hussain, and teacher of female vocalists Anayati Sunyari and Pukhraj Bibi.

He died in Lahore in 1970.

Mehruddin Khursheed

Son of Mohammad Boota, Mehruddin Kursheed was born in Lahore in 1900. Mehruddin learnt the art of sarangi playing from Mian Ditt Khan. His other music teachers included Ustad Imamdin Sialkoti and Mian Faqir Bukhsh Peshawari. Apart from being a good sarangi player he was also a good singer, actor and music director. Prior to Partition he was associated with Bombay film industry as a singer, actor and instrumentalist in the nineteen thirties. He moved back to Lahore in the mid nineteen forties. After Partition he worked in the film industry as an instrumentalist and worked with reputed music directors. Mehruddin Khursheed was the uncle of great sarangi players Nazim Ali Khan and Fazal Khan. Mehruddin taught many reputed female singers like Khurshid Bai, Iddan Bai, Inayat Dherowali and Malika Mehr Nigar of Jammu. He passed away in Lahore in the late nineteen sixties.

Fazal Khan

Fazal Khan, born in Shahalmi in Lahore in 1900 was the son of Miran Buksh, a tabla player. Ustad Fazal Khan was not only a good vocalist in his youth but was also an accomplished sarangi player. He got his vocal and classical music training from the famous Ustad Piyaray Khan of Gwalior Gharana. Ustad Fazal khan learned the art of sarangi playing from his uncle Nikkay Khan of Lahore. He used to be a regular feature at takiya mirasiyan, accompanying great vocalists and also playing solo. Among his famous disciples are his son, the distinguished music composer Master Manzoor, his son and sarangi player Ahmed Hussain Khan and his son and musicologist Professor Basheer. He died in Lahore in 1945.Barkat Ali Khan

Born in 1901 in Lohari Gate Lahore, Barkat Ali Khan was the son of Mian Billay Khan. He learnt the art of music and sarangi playing from his father and later honed his skills under Patiala Gharana’s Ustad Ashiq Ali Khan. During his youth, he was a regular at the Takia Meerasian in Mochi Gate and would be seen practicing with Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Barkat Ali Khan was also an excellent vocalist and was highly regarded for his teaching skills. Following Partition, Barkat Ali Khan joined the film industry and became an assistant of the famous composer Khawaja Khurshid Anwar. The maestro died in Lahore in 1976. Amongst his disciples, his son Mohammad Aslam Khan who played the sarangi died in Lahore in 2008.

Faqeer Hussain (of Chuna Mandi, Lahore)

Faqeer Hussain was born in Chuna Mandi, Lahore in 1902 in a family of reputed sarangi and tabla players. He was the first cousin of the illustrious tabla player Mian Qadir Buksh of Punjab Gharana. Faqeer Hussain’s father Hussain Buksh died quite young. He got his initial lessons in music from his grandfather Kheraat Ali, who was a singer. He learned the art of sarangi playing from Ustad Ghulam Nabi Dad Khan of Bhawani. He used to practice a lot in Takya Kabutar Shah, Gali Mirasian Wali, Chuna Mandi Lahore. Before Partition Faqeer Hussain traveled to Delhi, Mumbai, Calcutta and other parts of India to perform in different music conferences. After Partition he worked in almost all the major music centers like Lahore, Karachi, Rawalpindi, and Multan and accompanied such singers of repute. He worked in Radio Rawalpindi, Peshawar and Muzaffarabad in the early to mid sixties. His most prominent disciple is Surraiya Multanikar. He died in Lahore in 1982.

Ghulam Mohammad

Ghulam Mohammad Khan, born in Lahore in 1905 was the son of Ali Buksh Khan, grandson of Meeran Buksh and great grandson of Mian Nabi Buksh, all sarangi players. He learned sarangi from his father and also took sarangi lessons from Mian Billay Khan of Lahore. He performed all over India, mostly in private mehfils and takyas and accompanied famous vocalists of his times. In Muhallah Samyan, located in Bhaati Gate Lahore, he had his own baithak, where many famous musician of their times used to perform. His son Bakshi Wazir, famous music composer also learned sarangi from his father. He died in Lahore in 1982.

Ghani Khan, born in Lahore in 1922 was son of Fateh Din, a tabla player. He learned sarangi from Fazal Din, who was the disciple of Baba Ditt. His speciality was playing and accompanying the light classical genre like ghazal and thumri, geets etc. He mostly accompanied the courtesans of Lahore. He also worked in the film industry as a musician and died in Lahore in 1996.

His elder brother Mohammad Ali, a good sarangi player was equally good in sarinda and dilruba. He was the disciple of Hussaina Machi. He was amongst the very few sarinda players in Pakistan and was comtemporary of famous sarinda player Munir Sarhadi.

Baba Ditt was also the teacher of Mehruddin Khursheed.

Ghani Khan

Mohammad Ali

Nazim Ali Khan

Nazim Ali Khan born in Shahalmi, Lahore in 1928 was the son of sarangi player Rahim Buksh. Nazim Ali Khan started learning sarangi from a very young age from his grandfather Ustad Nikkay Khan. In his younger days as a sarangi player, he practiced in Takya Mirasian, and accompanied such great singers as Aashiq Ali Khan, Umeed Ali Khan, and Bade Ghulam Ali Khan etc. He also worked in films as a musician. In the nineteen fifties he became the disciple of Ustad Akhtar Hussain Khan of Patiala. In the mid nineteen sixties he joined Radio Pakistan Lahore, and served there as a staff artist till his death. He was a great accompanist and a very able soloist. He was equally good in the light classical and ghazal genre. He died in 1998 in Lahore.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM MEERAT

Allah Rakha (of Meerat)

Hailing from Meerat, Allah Rakha born in 1930 in a family of sarangi players was trained by his paternal uncle Rahim Buksh Khan and father Mian Jan Khan. He migrated to Pakistan in 1951 and was immediately offered employment in Radio Pakitan Peshawar. He was transferred to Radio Pakistan Dhakka, where he served until 1971 but was later posted to Rawalpindi, Hyderabad and finally Karachi. Allah Rakha Khan a regular accompanist to classical musician at Radio and Television. He passed away in 2002 following a performance with Farida Khanum at Mohatta Palace in Karachi.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM MEWAT

Abdul Ghafoor Khan

Born in 1906 Adbul Ghafoor Khan hailed from the family of sarangi players from Mewat. The tradition of sarangi playing in the family dates backs to his grandfather Kinnar Khan, who was a court musician in the State of Alwar. Adbul Ghafoor Khan took initial lessons in sarangi playing from his father Madar Buksh, later he became formal disciple of Ustad Ghulam Nabidad Khan of Bhawani. He also learned the intricacies of classical music from Kirana Gharana greats like Abdul Karim Khan and Shakoor Khan. After Partition the family shifted to Hyderabad, Sindh. Ghafoor Khan also worked in Radio Hyderabad and died in 1979. Amongst his prominent disciple in sarangi playing are his son Abdul Majeed Khan and nephew Chahat Khan.

Ameer Khan

Ameer Khan, born in 1924 in Mewat, received his initial training in music from his father Paltu Khan, and then learnt from Ustad Chotay Khan, who was a famous sarangi player of AIR Calcutta. Ameer Khan also received sarangi lessons from the famous Khadum Hussain Khan, who worked in AIR Bombay. Ustad Ameer Khan initially joined AIR Dhaka, worked in AIR Calcutta and Bombay. Afterwards he toured extensively all over India and accompanied many great singers of his times. After Partition he migrated to Pakistan and settled in Hyderabad and joined the radio.

Apart from competent sarangi player he was also a great teacher. The list of his disciples is huge and include big name like Ustad Majeed Khan, Ustad Ramzan Khan, Shamsuddin Khan, Zulfiqar Khan, Mazhar Hussain Khan. He died in 2001.

Abdul Majeed Khan

Born in Mewat in 1930, Abdul Majeed Khan was trained by his father Ustad Abdul Ghafoor Khan. Later, Majeed Khan became the disciple of Ustad Ghulam Nabidad Khan of Bhawani and the illustrious sarangi player of the Kirana Gharana Ustad Shakoor Khan. Following Partition, Abdul Majeed settled in Hyderabad, Sindh and was recognized amongst the foremost sarangi players of Pakistan. Ustad Abdul Majeed was an accomplished soloist and a great accompanist. He regularly performed with Roshan Ara Begum, Ustad Umeed Ali Khan, Ustad Manzoor Ali Khan, Ustads Nazakat Ali Khan Salamat Ali Khan, Ustad Ghulam Rasool Khan, Abida Parveen, Iqbal Bano etc. The maestro passed away in 2001 and was posthumously awarded the Pride of Performance. Amongst his disciples, his brother the renowned harmonium and composer Rasheed Khan is prominent, as well as Zaamin Ali and Faisal Aziz who are making their mark in vocal music.

SARANGI PLAYERS FROM MURADABAD

Hamid Hussain

Hamid Hussain, born in Rampur in 1923 received his initial training in sarangi from his father Abid Hussain and grandfather Haider Hussain Khan and later from his maternal uncle Ustad Ali Jan of Rampur.

Hamid Hussain Khan joined All India Radio Delhi when he was only fifteen years old. After the death of his grandfather he shifted to Bombay in 1939 where he accompanied most of the senior vocalists of his time including Ustad Faiyyaz Khan, Ustad Ameer Khan, Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Begum Akhtar, and Roshan Ara Begum. After 1947 he joined Radio Pakistan Dhakka and then was transferred to Karachi where he served until his death in 1980. He was an accomplished sarangi player having equal proficiency in playing all genres of classical music. He played with all the leading vocalists of Pakistan and was a storehouse of traditional bandishes.

Ustad Hamid Husain Khan was also a great teacher; the list of his professional and amateur students includes names such as Dinaz Minwal, M.Iqbal, Dr Regula Quraishi, Ustad Salamat Hussain (flutist), Habib Wali Mohammad and host of others.

Zahid Hussain

Born in Muradabad in 1930, Zahid Husain trained by his maternal grandfather, Ustad Ali Jan Khan, started accompanying senior vocalists of his time at the age of thirteen. He migrated to Bombay where his elder brother Hamid Husain had already established himself at All India Radio. However, Zahid Hussain chose to join the film industry. After six years stay in Bombay, Zahid went to Muzaffar Nagar; a place where music was patronized and a supportive atmosphere for classical art forms exit.

Zahid Hussain migrated to Pakistan in the late fifties and settled in Karachi where he joined Radio Pakistan as a staff artist and continued working there till his death.

During his career at The Radio, he accompanied recognized vocalists of the country including Ustad Nazaakat Ali Salaamat Ali, Ustad Amaanat Ali Fateh Ali, Mehdi Hasan, Fareeda Khanum, Iqbal Bano, Abida Perveen, Ghulam Ali etc. He was a versatile musician caapable of playing classical, semi-classical and light music including ghazal, geet and film songs. He died in Karachi in 1988.

Wahid Hussain

Wahid Hussain born in 1927 in Moradabad, became the disciple of sarangi player Ustad Tajammul Hussain Khan. Following Partition, he settled in Karachi where he worked at Radio Karachi as a staff artiste. The Radio Pakistan signature tune was composed and performed by him. Radio Pakistan provided the maestro with ample opportunities to perform with vocalists of the stature of Roshan Ara Begum, Ustad Amanat Ali Khan- Ustad Fateh Ali Khan, Ustad Nazakat Ali Khan – Ustad Salamat Ali Khan, Farida Khanum, Taj Multani and Mehdi Hassan. He was in particular, the regular accompanist to Farida Khanum during her performances in Karachi. Wahid Hussain Khan also made his mark as a composer and poet. Ghazal singer Azra Riaz is amongst his most prominent disciples. Wahid Hussain Khan passed away in Karachi in 2004.

Left Hand Playing Technique

The sarangi’s three melodic strings are stopped not with the tip of the fingers but with the part of nails just below or above the cuticle, with the finger tips touching the fingerboard. Left hand finger technique is completely unstandardized, especially in Pakistan. There are as many techniques as there are players. The left hand fingering technique can be divided into two main categories i.e. four fingers technique and three finger technique. The four fingers technique is an older and complex technique which is believed to be more suitable for the vivid movements of lighter genres like thumri. The three finger technique is a more recent evolvement and is believed to be more streamlined and better suited for solo playing in particular (Bor 1987: 30).

In India the four fingers technique has almost become obsolete and the three fingers technique has become a standard. In the classical music of Pakistan there is diversity of trends, and continuity and originality of traditions, whether it is vocal or instrumental music. Same holds true for the sarangi playing technique. Most of the sarangi players of Pakistan, past and present, use the four fingers playing technique.

The left hand fingering systems that are prevalent in Pakistan are given below:

Three fingers technique

On the first melodic string

S R G m P D N S R

0 1 1 2 2 3 3 3 3

On the second and third melodic strings (If the second string is tuned to pancham)

S N D P m G R S

2 2 1 0 2 1 1 0

Four fingers technique:

On the first melodic string

S R G m P D N S

0 1 1 2 2 3 4 4

On the second and third melodic strings (If the second string is tuned to pancham)

S N D P m G R S

2 2 1 0 2 1 1 0

Four fingers technique of Amritsar and Jalandhar:

On the first melodic string

S R G m P D N S R

1 1 1 2 3 4 4 4 4

On the second and third melodic strings (If the second string is tuned to pancham)

S N D P m G R S

2 2 1 0 2 1 1 0

For example a sarangi player using the three fingers technique can use all the three fingers in lower as well as in upper tetra chords. Moreover the use of kuns with different fingers also become more prominent. The kun with the forth finger is also employed, as evident from the longer growth of the little finger’s nail on most of the sarangi players using the three fingers technique. In a personal communication, Shafqat Ali Khan, the son of Munshi Ghulam Ali Khan of Hoshiarpur, told me that he follows the following fingering system, which was told by his father:

S R G m P D N S R

1 1 1 1 2 3 3 3 3

So in this case according to him, while playing raga Malkauns (S g m d n S) on sarangi he uses only the first and the third finger. But while playing a thumri in raga Piloo (see video example: ShafqatAli-piloo) he used second finger for rendering the komal gandhar in avroh phrases which further reinstate the point that there are as many fingering system as there are players.

In a personal communication, Allah Rakha Khan told me that a particular note should not become dependent on a particular finger; rather one should be very flexible. In a practical demonstration he played same notes with different fingers to convey his point. (See video example: AllahRakha-FlexibleTechnique)

On the whole it seems true that four fingers technique is better suited for playing the lighter genres like thumri. It does not employ that it is not suitable for khayal rendition. Natthu Khan and Hussain Buksh of Amritsar who belong to four fingers playing technique (which will be discuss in detail in chapter 4), were excellent khayal players. But it seems true that by using four fingers technique one can do greater justice to a thumri rendition. The reason behind this assertion is that if a sarangi player places four fingers on four different notes, there is less sliding of fingers on the finger board, hence there is a greater chance of quick maneuvering and playing with the notes. It make easier for the player to produce the typical ornamentations of thumri like khatka, murki, behlawa, zamzama, short and brisk taans especially of tappa type, and brisk and vivid movement between adjacent notes (see video example: AllahRakha-Pahari)

Another technique of playing sarangi especially while accompanying, is using the fixed tuning for the main melodic strings. Every singer sings according to his or her own scale, whether first white, first black, second white etc. Retuning the sarangi for every singer becomes very cumbersome and time consuming. In such situations the sarangi players adjust the kharaj on the main melodic strings while maintaining the original tuning. For example if the main melodic string of the sarangi is tuned to the first black and the singer is going to sing from the second black the sarangi player can make the shudh rikhab as the kharaj and starts accompanying. Sarangi players also employ this technique while playing solo thumri, thus to avoid excessive crossing over of the melodic strings. (See video examples: AllahRakha-Pahari and BashirAhmed-NazimAli).

Another practice had been prevalent while accompanying the female singers. The female singers usually sing from quite a low pitch. If a female singer is singing from the forth black of the lower octave then it would be difficult for the sarangi player to tune the first melodic string of the sarangi to such a low pitch (because of the thickness of the string). In such cases the sarangi players usually tune the second melodic string to the kharaj of the female singer.

These entire examples shows that although there are a couple of systems of fingering technique but it is quite flexible and depend on the individual player, playing repertoire, genre, and scale.

Music Making Models

In Hindustani music there are two main melodic music making models in art music. As instrumental music developed into solo art form, the various modern instruments adopted these two basic models (Raja 2005: 103).

- The Gaiki (vocal) model:

This model is based on melodic continuity and the dominance of the melodic element over the rhythmic element

2.The rudra veena/tantkara model:

In this model plucking of the strings serves as the mode of sound activation. The act of plucking creates an element of melodic discontinuity as well as rhythm. This model offers a large range of stylistic and idiomatic options in terms of the balance between the melodic and rhythmic elements.

The predominant instrumental playing style in the twentieth century is that of sitar and sarod. Their repertoire, especially of sitar dates back to the mid eighteenth century. The compositions that are played on these instruments are called gat (Slawek 2000: 188).

The most predominant of these gats are the masitkhani gat and the razakhani gat.

History of Solo Sarangi Playing

The tradition of classical sarangi playing began in the early part of nineteenth century. During this period sarangi players had become formidable exponents in South Asian Classical Music, and were recognized as maestros in their own right. There art had become a part of the system of hereditary musicianship, giving rise to several distinguished families of sarangi players (Raja 2005: 337).

Towards the end of nineteenth century, the declining fortune of the sarangi gave rise to two distinguished developments. Some exceptional sarangi players abandoned the sarangi in favor of career as vocalists. The other significant development was the emergence of sarangi soloist. In the early part of 20th century solo performance of sarangi playing started emerging through such great sarangi players like Mamman Khan and Bundu Khan (Raja 2005: 338).

Mamman Khan belonged to the Delhi Gharana of vocal and sarangi players. Delhi Gharana is perhaps the only recognizable Gharana in sarangi playing because it seems to be an offshoot of vocal Gharana and contains a large number of distinguish vocalists. This Gharana contains relatively few sarangi players but these sarangi players did make history as soloists (Bor 1987: 129).

Mamman Khan was perhaps the first artist to play khayal or gaiki ang on sarangi (Bor 1987: 130). He paved the way for the solo performances of sarangi, which were taken to greater heights by his nephew and disciple, the great sarangi maestro Ustad Bundu Khan in the first half of the 20th century. In the later half of the 20th century, it was the great maestro Ram Narayan who single handedly elevated the status and stature of sarangi from a mere accompanying to a full grown solo instrument (Roy 2004: 205).

A Typical Solo Instrumental Performance

A solo performance based on the plucked instruments model (e.g. sitar) commences with the rendition of alaap, jor and jhala before the commencement of gat in a rhythmic cycle.

Alaap is an improvised process of gradual exploration and consolidation. It consists of exploring different combination of notes in all the three registers. It usually begins in the middle register, then descending to the lowest point of lower register and then gradually moving upwards (Sorrell 1980: 159).

After alaap when the full range of raga has been covered, it is customary to begin the Jor section. Indian plucked instruments usually include sets of drone strings known as chikari alongside the main melodic strings. Jor is the pulsed section in which the instrumentalist sounds the chikari strings in balanced alteration with the melodic strings. So chikari strings are important in maintaining the steady pulse throughout the jor section. The jor starts at a slightly faster tempo than the ending pace of the non-pulsed alaap and increases gradually (Slawek 2000:199).

The final section jhala is faster in tempo than the jor section and the chikari strings become more pronounced. Melodic strokes are followed by clusters of chikari strokes. Although not necessary, some musicians maintain the rhythmic cycle of sixteen beats through out the jhala section (Slawek 2000: 199).

After the jhala section an instrumentalist starts a slow paced gat, usually in a sixteen beat rhythmic cycle like teen taal. This is followed by a faster tempo gat and eventually the conclusion of the performance.

Hindustani classical music instruments can be linked with different genres of classical music. This is because certain instruments are suitable for certain type of music by the virtue of their making, playing and acoustics. For example bin, veena and pakhawaj are usually associated with dhrupad. Similarly sitar, sarod, sarangi and tabla are linked with khayal and thumri etc.

All the modern classical and semi classical forms of North Indian Classical Music like khayal, thumri, dadra, tappa etc. can be played solo on sarangi. Dhrupad is usually not played on sarangi.

In general the musical repertoires of bowed instruments like sarangi are not related to the core repertoire of plucked stringed instruments (tantkari ang). Until recently, the bow instruments did not have either a significant solo presence or stature in art music. Unlike sitar and sarod, they can not be said to have an independent music making model that has evolved as a tradition. (Raja 2005: 103)

Through the first half of the twentieth century, bow instruments like sarangi followed the vocal model because they were capable of producing sustain notes and the music of melodic continuity was their obvious territory (Raja 2005: 103). Bow instruments were designed explicitly as the closest possible way to explore and match the musical capabilities of the human voice (Raja 2005: 105).

But in the recent past the trends are changing and the wind and the bow instruments have started employing the languages and idioms of tantakara model also (Raja 2005: 105).

A khayal’s solo sarangi performance structure can either follow the typical plucked instrumental format or the bada khayal or chota khayal gaiki format.

As mentioned earlier a typical format of a solo plucked instrumental performance (eg sitar) includes an alaap, jor, jhala, and gat (composition) in the same sequence. All this can be played solo on a sarangi. Alaap is followed by jor that can be played on sarangi by introducing a steady pulse. Although there are no chikari strings on the sarangi but according to Slawek (2000:199) “Bowed string instruments and wind instruments, in contrast, accomplish the pulsating effect with stress and accent, in a manner similar to vocal nom-tom performance”

The playing of jhala on sarangi has always been an issue of controversy. Some modern sarangi players do play jhala on sarangi, but most of the players omit it entirely.

According to Sorrell (1980:159) “The curtailment of jor and even the complete elimination of jhala, and, instead, the performance of taans is a characteristic of solo sarangi playing”.

“The ability of an instrument like sarangi to play jhala is in some doubt. Nowadays, jhala is associated with plucked instruments such as sitar and sarod, and consists of a rapid alteration of melody string with repeated notes on the drone string (chikari)” (Sorrell 1980: 160).

The jhala can be simulated on sarangi but as said earlier the problem is that it does not possess chikari strings. One solution to this problem is to play a stopped note followed by several rapid strokes on the open string. Other methods of playing jhala on sarangi can be through rapid repetition of single notes, or by irregular phrasing and repeated notes, with an emphasis on Sa, to create an impression of jhala (Sorrell 1980: 160).

The other performance structure of solo sarangi playing is modeled on slow tempo bada khayal or medium to fast tempo chota khayal. In the bada khayal format the performance usually commences with a short non pulsed alaap, followed by the introduction of tabla and rendition of a bandish (composition) in vilambit lai. As in vocal khayal performance, a fast tempo bandish follows the slow tempo vilambit khayal. It is a common practice to omit the antra in solo sarangi performance. A medium paced bandish in mudh lai is sometimes rendered after the vilambit khayal.

The chota khayal format contains a single medium tempo composition, normally without an elaborated alaap. The tempo of the rendition generally remains the same throughout the performance with only marginal acceleration. The duration of the performance is considerably less than bada khayal.

A hybrid approach containing elements of the above mentioned formats can also be employed while playing solo sarangi.